Pinched or Trapped Low Back Nerve – Sciatica

Many patients will come in saying “ I think I have a pinched or trapped nerve”. What exactly does this mean? What is a “pinched nerve”? Does a pinched nerve cause back pain? Is there really such a diagnosis? Well, yes and no.

In order to delve into this concept, we need to initially start with very simple terms, and a brief anatomy lesson. The human nervous system is broken down broadly into two parts. These are the central nervous system or CNS and the peripheral nervous system or PNS. The CNS is composed of the brain and spinal cord, which branches off into the spinal nerves, feeding the rest of the body. When these spinal nerves exit the spine, the PNS starts. Thousands of nerves exist in the human body, in essentially every body part; these nerves are all part of the PNS.

The biggest nerve in the human body is the sciatic nerve, which is formed in the pelvis from multiple spinal nerves, after they have exited the spine. Anatomically, the sciatic nerve travels down the leg, and can cause leg pain. Before the advent of modern technology, when people had nerve related leg pain or buttock pain, it was presumed that this was caused by compression or damage occurring to the sciatic nerve. The term “sciatica” was born based upon the above concept. With the advent of modern technology, and MRI in particular, we now know that this is incorrect. Although the sciatic nerve can, in fact, cause leg pain, and get compressed or “pinched” by the piriformis muscle in a region called the “sciatic notch” (a condition called piriformis syndrome), this is very rare. Sciatica, in over 95% of cases actually has nothing to do at all with a sciatic nerve problem or compression…aka “pinching”.

A far more common cause of nerve related arm or leg pain is compression of a spinal nerve. This condition is called “radiculopathy” . In most cases, “pinching” of a lumbar spinal nerve causes buttock and leg pain, and pinching of a cervical spinal nerve causes shoulder and arm pain.

How are pinched nerves identified by an Osteopath? In addition to obtaining an astute history of the patient’s symptoms, and performing a detailed physical examination, such as a complete neural examination other measures can be taken. Imaging studies such as X-ray or CT scan provide good detail of actual bony anatomy of the human body, but very poor visualization of soft tissues and nerves. The best test to visualize the spinal nerves is an MRI, and this is considered the “gold standard” imaging study that Osteopaths and Doctors prefer. MRI is performed with magnets, and this can interfere with the function of some medical devices such as pacemakers. If an MRI cannot be performed, a CT scan is often needed, usually in conjunction with an injection of dye into the spinal canal to visualize the spinal nerves. This dye injection procedure is called a “myelogram”.

In some cases a procedure called an electrodiagnostic study, or EMG/NCS, can assist Neurologists and Spinal surgeons in identifying the affected nerve. This is a neurologic test involving electrical discharges and small needles that are inserted into various muscles that can provide information on the actual function of the various nerves in the arm or leg where symptoms are located

. This test can also identify if nerves other than spinal nerves are responsible for the symptoms that are experienced anywhere in the arm or leg.

A commonly debatable topic is whether or not lumbar spinal nerves can cause back pain. Generally, it is accepted that they can, but usually just lateral of the midline, off to the right or left side of the spine. An area called the sacral sulcus, is often painful when spinal nerves are compressed. With severe compression and inflammation of the spinal nerves however, it is generally expected that symptoms will travel distally, down the arm or leg supplied by the respective nerve affected. This is called a “dermatomal pattern”.

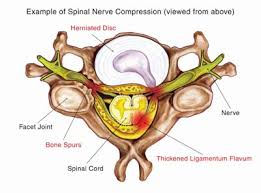

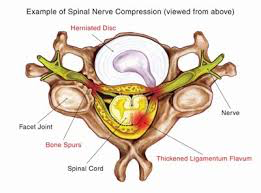

Pinched spinal nerves can develop suddenly or gradually. Sudden compression usually occurs in the setting of an acute joint problem called a “herniated disc”, also discussed in more detail elsewhere. More gradual compression usually occurs over time due to bony changes that develop with the aging process and development of bony overgrowth and bone spurs. If there is narrowing in the spine in the areas where the nerves are located, this is called “stenosis”. If the center part of the spinal canal is stenotic, or narrowed, this is called central stenosis, and if the lateral part of the spine is narrowed, where the spinal nerves are trying to exit from the sides, this is called foraminal stenosis or lateral stenosis.

Gradually developing chronic pain and functional decline coming from the pinching of spinal nerves due to bony stenosis is generally considered to be surgical diagnosis. The pinching of spinal nerves from a sudden (or acute), soft disc herniation can often be treated non-surgically with avoidance of activities that cause pain, appropriate physical therapy, oral medications, and frequently x-ray guided (also known as fluoroscopically guided) selective nerve root blocks or epidural steroid injections at the area of irritation and inflammation.

Since the human body is generally so adaptable to changes that occur during the ageing process, often compressed, or pinched, spinal nerves are identified incidentally and do not cause any symptoms at all. It is natural for this compression to gradually develop during the ageing process. It is important to realise that unless a compressed nerve is causing symptoms such as severe pain, weakness, or numbness leading to longstanding functional changes, that no treatment is necessary. Although Osteopaths and Surgeons can address seemingly significant findings on a picture, we treat patients and not imaging studies. It is exceedingly rare that a patient with no symptoms will require any kind of aggressive interventions, such as spinal surgery.